Part 3 1946-1972

Abegg had spent Christmas and the New Year in jail. Whatever evidence convinced the American military, she was released from prison on 21 January 1946 and left Japan for Switzerland three weeks later. Here she worked as a journalist at Die Weltwoche, a Swiss magazine based in Zurich. At least initially she turned away from travelling to the Far East and instead travelled to and produced reports on the Middle East, Pakistan and India.

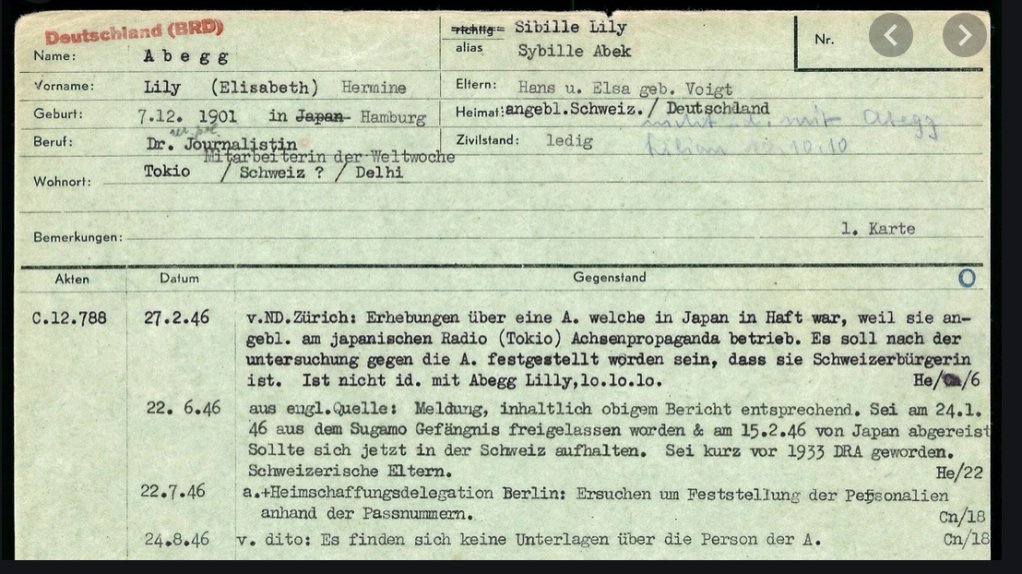

Abegg could not, though, escape her past. The federal prosecutor’s office in Bern began collecting information and opened a file on her after her return. This was not helped by the fact that a few days following her release from Sugamo, a Christmas greeting card from 1944, sent by the local German community, had been discovered. This Abegg had signed. The card carried the message, ‘It is our common desire that Germany’s Adolf Hitler succeed in his difficult battle of fate. Heil Hitler!’

In Switzerland she was labelled by the security services as a potential Nazi sympathiser. They were suspicious that she might act as a messenger between German nationalists who had remained in Japan and those in occupied Germany. Abegg’s telegrams to Japan were intercepted. However whatever these contained did not hinder her career.

In the late 1940s she began investigating the story of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. During World War II, Netaji made unsuccessful attempts to free India from the British rule with the help of Nazi Germany and Japan.

He was supposedly killed in an air accident over Taipei in 1945 but the truth of this was questioned. Abegg wrote to Netaji’s brother, Sarat Chandra Bose on 9 December, 1949 – a letter intercepted by the Indian intelligence at the Elgin Road Post Office – where she writes, ‘I heard in 1946 from Japanese sources that your brother is still living.’ She added that she had heard from other press sources that he might be living in Beijing but added that the good ties between Indian and Switzerland prevented her from telling everything too openly about Netaji and that since she had not been in India, she could not take one side only and be against the government. Bose was to also claim, ‘She came to meet me in an interview at Glyon. In course of the interview I gathered that she was in Japan at the time of Japan’s collapse in the last world war. She had contacted important and informed British and American sources, and none of them believed in the air crash story or that Nataji was dead.’

Even though she had stopped visiting the Far East, in 1952 she published The Mind of East Asia, over three hundred pages long, and where she postulated that the mind of the Westerner and the East Asian were entirely different ‘particularly in their psychological constitution.’ It is a lengthy, thorough, scholarly and remarkably well-argued treatise, and even today should be read by anyone who wants to understand the Japanese and Chinese.

A year later she had published another well received book, this time on the Middle East. Written for German readers, Arabishe Politik Heute was intended to fill a gap in their knowledge of the politics of the arab world. She interviewed many leaders including the newly established rulers in Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Iraq. In the first half of the book she takes the reader on a tour of various Arab countries and writes her portraits of the leaders in the region. In the second half, she tackles some of the major issues facing the region: social tensions and the rise of nationalism; the conflicts with Israel; the issues of Suez and the Sudan; the abundance of oil and the paucity of water, and the problems of defence. A reviewer said the book was concise, balanced but incisive.

By 1954 she returned to Tokyo as a Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung correspondent, as well as freelancing for three Swiss newspapers and magazines. She made numerous trips across the Far East and Southeast Asia.

However these trips were not as benign as might be seen on the surface. She was being monitored by Britain’s Security Intelligence Far East, who were based in Singapore. They noted that she was using different Swiss passports and was travelling from Japan to China, to Hong Kong and into Indo-China. On her passports, she variously described herself as a ‘journalist’ or ‘diplomatic courier’ The security services noted that ‘it is unclear for whom she is now working.’ It was also in a 1956 note that William Drower (who was a PoW in a Japanese camp and later went on to a distinguished career as a diplomat) wrote in a note the comment ‘@Tokio Lily as I remember her.’ (However, that is the only reference that I have found to her being given this nickname.)

Of course it was this time that tensions were still rife in the region despite the ending of the Indochina war between the French and Vietnam. Nor was it a safe place to travel. She could have been working for any intelligence service and that included the Swiss.

However she then dropped out of the security services interests but remained a prolific writer about the region.

Her brother Hans died in Yokohama in 1957 shortly after returning from a trip to the U.S. with his wife Yuri, and was buried in the city’s Foreign Cemetery in the same grave as their mother.

That same year her book Im neuen China was published.

Abegg finally left Tokyo in 1963 and returned permanently to Switzerland. A farewell dinner was held at the Foreign Correspondents Club when she was presented with a silver cigarette case.

Back in Zurich she continued to write but she also worked as a radio and television journalist.

In 1966 she published Vom Reich der Mitte zu Mao Tse-Tung.

Her next book released in 1967 was China und Vietnam: Herausforderung unseres Gewissens. China was now her key interest as the country began to rise to prominence in global affairs. In an article in Die Weltwoche in 1969, and entitled Hass und Hassliebe, she argued, for example, that Russia and not the U.S. was now China’s main enemy.

On 13th July 1974, she died of a heart attack while taking a holiday in Samedan. She had been writing articles up until her sudden death, and her latest book, Japans Traum vom Musterland. Der neue Nipponismus had just appeared.

She had remained unmarried.

In total she had published ten books and innumerable articles. Abegg was said to be an old school orientalist, with her writing not so much based on in-depth academic research but her own experiences and the knowledge she gained from the people she knew and met. She herself was happy to admit this but her depth of knowledge was remarkable.

From the 1930s until her death she criticised Eurocentrism, and she also rejected the way that writers from the West created fantasises about Asia based on romanticism and myths, and not on a well-grounded knowledge and experience of the region. She never learned to read Japanese well but neither did she consider her lack of knowledge of the Japanese language as an obstacle to understanding her adopted country.

Her intelligence, knowledge and contacts made her a natural spy. That she was part of the network of spies for the Axis countries in wartime Tokyo should not be doubted, nor that she continued to spy post war – at least for a few years. Not that this was an unusual side occupation for journalists. They were often recruited to become part of a network. The British did it. The Americans did it. But who exactly was she spying for? The straightforward answer is that it was for the Germans. But if this was the case, would she have been released so quickly after being arrested? Was she acting as a double agent all this time? Questions that at the moment cannot be answered.

There is no evidence that she was coerced or an unwilling supporter of the Nazi Party, although the extent of her support is unclear as is the ideology behind it. The Nazi Party’s attitude to women would appear to be the antithesis of the life that she herself led.

As we now know, the Swiss while neutral undertook a number of actions that supported Germany during the war. Several thousand Swiss joined the German army, primarily from the German-speaking regions, which of course was where the Abegg family was from. That said in 1943 the Swiss government decreed that all Swiss citizens who had cooperated with the Third Reich should be deprived of their nationality. Abegg did not fall foul of this.

So a complex woman. Passionate. Tireless. Brave. Supremely intelligent. A brilliant journalist.

Key Sources

- British Secret Service declassified files. British National Archives.

- Tokyo Rose / An American Patriot: A Dual Biography. Frederick P. Close.

- Foreign Correspondents in Japan By Foreign Correspondents Club. Japan.

- RP Kramers , ” Lily Abegg in memoriam “, in Asiatische Studien , 28, 1974, 81-84.

- Internationales Biographisches Archiv/37, Munzinger.de.

- Clark Lee, “Swiss Woman Writer Denies Helping Japs: Only Woman on McArthur ‘Wanted’ List,” Various newspapers, 18 September 1945.

- Japan and Germany in the Modern World, Bernd Martin.

- Jahresbericht 2018/2019. Annual Report 2018/19. Freie Gymnasium Zurich.

- China’s Erneuerung: Der Raum als Waffe [China’s Renewal: The Land as Weapon], Frankfurt: 1940. Translation from the German by Adam Cathcart.

- Ancestry.com